This instalment is available in text and as a podcast — but, I recommend listening in: it’s a story about sound, and I’ve put lots of care into bringing it to life.

Originally published in Scuff.

I’ve been telling friends I’m writing a piece on Merzbow.

Who? “I’ll just... play you some.” The sound of a forest fire in an artificial Christmas tree warehouse bursts from my phone speaker. It receives a pained expression, but there’s something else, too: maybe it’s intrigue, maybe concern. I turn it off.

The artist behind these sounds is Masami Akita. He started Merzbow while a student of painting and art theory in Tokyo, and later wrote for magazines on masochism and Japan’s erotic kinbaku bondage art. “It’s supposed to be so extreme it causes physical pain,” I explain. “It’s supposed to be ugly.”

Modern art has often flirted with ugliness; we could start with Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain.

When first presented with the work, in 1917, The Society of Independent Artists (which Duchamp himself co-founded) rejected the work on the belief that an object men piss in could not be considered art, even if it was signed, dated and laid on its back. It would be threatening to female viewers’ modesty, they thought.

But the object itself was not disgusting; it merely had disgusting connotations. As Beatrice Wood wrote of the piece in 1917, the “fountain is not immoral, that is absurd, no more than a bathtub is immoral. It is a fixture that you see every day in plumbers’ shop windows.”

The form is simple, comprehensible, banal — only ugly by negation: ugly because it is not beautiful. It is a Minimalist Ugliness. Inoffensive on its own terms, and with the potential (if we give particular meaning to it) to become beautiful.

That pained expression on my friends’ faces — exposing them to Merzbow outside a lecture theatre — it was my own reaction to seeing the paintings of Eugène Leroy in the Louisiana Museum three years ago, at once repulsed and transfixed. Every colour, every texture, every relief is forced onto the canvas until it becomes a flesh: bubonic, lesioned, necrotised; rotting open to reveal a vile interior we would rather keep hidden.

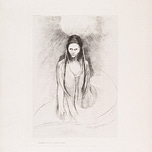

Leroy called his paintings nudes, but it takes many minutes of scanning across the canvases to find the barest suggestion of a recognisable shape; perhaps it isn't there at all. I may have simply fabricated the curve of the lounging woman — seeking reason in the revolting, putrid image before me. If they are nudes, they depict something more naked than the unclothed body: they are dark, unmediated projections of the unconscious.

This is Maximalist Ugliness — not a negation of beauty, but a counterpoint: a unique aesthetic in its own right.

But do these paintings quite reach the maximum of ugliness? You can never repeat the sublime disgust of the first encounter with Leroy. Spend long enough with this flesh and you might turn it into an idea; start seeing, as I did, a figure where there is none.

So no, not quite: Maximalist Ugliness must be constantly vile. And, therefore, it must constantly change.

In music, beauty happens by rationalising frequency and duration into conscious signals: tone, harmony, rhythm. In the shadow of music is noise.

Noise is something ugly, difficult, meaningless: like Nietzsche’s spirit of gravity we push it back, repress it, try to overcome it. In Paul Hegarty’s book Noise/Music: A History it is described as ‘excess to the normal musical economy,’ something to be ‘excluded as threat’. But, like gravity, noise is inevitable, carried by every signal as a shadow. Even in the vacuum of space, the white noise of blood moving through your ears would be ever-present.

John Cage famously revealed these ‘incidental noises’ in the silent score of 4’33”. A conductor stands on stage, turning the pages of sheet music without moving her baton. You can’t bear to watch, to listen: but what are you listening to, anyway?

Now flip the coin. Rather than open up space for the noise we normally ignore, fill every seeping, defenceless nook and diffident cranny of it with noise we cannot bear.

This is Merzbow.

White noise is the product of many audio frequencies playing at the same volume — like the equal intensity of all frequencies of light producing white colour. It is a Minimalist Ugliness — ugly by not being beautiful.

To reach Maximalist Ugliness, the noise must demand our entire attention; overwhelm our senses, resist our will to suppress it to the background. To do so it must permit just a hint of signal, like Eugène Leroy’s barest suggestion of a human figure, which we, as the viewers, attempt to complete.

In this way, the experience of the work is not made in the object itself, or the ideas around it — as in Minimalist Ugliness — but in the tension between the work’s incompleteness, its noisiness, and the viewer’s imaginative desire to understand it, to turn it into signal. The longer this tension is held, the greater the effect, and the deeper the relationship between subject (you) and object (the work of art).

Merzbow introduces signal by wrestling with his noise, attempting to capture it, tame it, mould it towards a music we can recognise. Again, however, the suggested destination is never given: any rhythm soon disintegrates; its volatility escapes the artist’s control, and explodes into a different and equal violence.

We hear these traces of rhythm, melody, dynamic shifts, and repetition, and wrestle with them, too: attempting to complete the journey, make sense of the distortion. But, where this might be possible with a painting (which cannot change with time, even as our perception of it will), it is impossible with noise. Merzbow stages a revolution every instant. Any respite is offered only to exacerbate the next attack. Blinded, and bound in kinbaku, we do not know what force will assault us next. By constantly changing, the noise denies us the ability to translate it into signal.

Perhaps we could listen to just a single ‘song’, again and again, forcing repetition. We could learn its textures and microstructures; anticipate them, dull their edges. But this too is accounted for. There are close to four hundred Merzbow albums, enough to subject ourselves to for weeks on end, ever new, and ever now.

Thus, the reaction to Leroy’s fleshly paintings — repulsed and ensnared — is made indefinite. We arrive at Maximalist Ugliness.

But why? Why do I argue for an aesthetics so vile that perceiving it causes physical pain?

I’d known about Merzbow for a while before I chose to subject myself to it, two years ago.

Something had happened, or I had done something. Either way, the boundary separating my conscious mind from my unconscious being had broken — or rotted — to reveal an interior I had tried to keep hidden.

It took a few weeks to recover, and I was fragile; left raw like a graze that hasn’t yet healed over. Every synapse was firing randomly, at equal intensity. No signal, all noise.

Unable to think, unable to really have a conversation, or describe what was going on inside, I walked — through the dusty heat of the city, trying to escape my brain. It was high summer and the sky was white.

I listened to music as I walked. But it was strange; what was normally beautiful had become ugly. I tried to understand rhythm, melody, tone, and texture, but all were out of grasp.

There’s a short playlist I made in those weeks: the sludge of Divide And Dissolve; the hanging dissonance of Simon Fisher Turner’s score for Derek Jarman’s film The Garden; the concrete black-metal of Liturgy’s HAJJ. But none of these could quite overwhelm the noise of my own psyche.

So I put on Merzbow. Maximalist Ugliness — demanding to the point of devouring my consciousness; to the point where lucid thought becomes impossible.

It was a punishing listen, until it became submission. I surrendered the idea of control, the idea of understanding. I gave up and gave in to the violence, floating out-of-body as I walked the city, relinquished in the noise from the noise, relinquished from myself.

A year passed; I forgot about Merzbow, forgot about the idea I had for a work of art that would visualise Maximalist Ugliness.

A 4,096 by 4,096 pixel square would be projected on a wall. Every pixel would be assigned a random value from the sRGB colour space (made up of 16,777,216 individual colour values, or 4,096 x 4,096). A new arbitrary image would be produced multiple times a second — changing at random intervals. I needed a way to corrupt the system somehow, to introduce a hint of signal to the noise, but I hadn’t worked that part out yet.

I liked the idea that, in one ephemeral frame out of uncountable millions, a picture of a dog might be projected; a perfect gradient, or an image of an unsolved murder. Like in Fight Club, where Tyler Durden splices single frames of pornography into children’s films, it would happen too fast for the viewer to know if their own internal fantasy was playing tricks on them.

Nietzsche’s gravity was a gravitas — all that was serious in the world, all that was heavy. If only we work hard enough today, we can reach the land of milk and honey, eventually. If only we are pious enough, today, God will grant us Heaven in the next life. An addictive delusion, he said. The only way to overcome gravity was to make anti-gravity: to overcome all that was serious, we must laugh.

Consciousness, the ego, floats at the surface; but it holds up the whole system. Dissolved, and flailing for something to hold onto, it drags everything into chaos, into noise.

But Merzbow’s noise is anti-noise; anti-consciousness. He laughs at the conscious: makes thinking impossible; chokes it out, squashes it under unbearable mass.

So consciousness falls; and the unconscious rises, wanders.

A year had passed. Another in the six years of the relationship that had defined my adolescence. The relationship that — with inexorable slowness and acrid cruelty — fell apart at a distance last summer, rotting open.

I was fragile again; left raw like a graze that hasn’t healed over. Every thought was vile and I couldn’t stop thinking — second-guessing my second-guessing. All signals fired at once, becoming noise.

My bike was broken; I had to walk. It was high summer and the sky was white. I returned to Merzbow.

Noise erupted; noise changed in character but not intensity; noise halted to begin again. Layers of noise cancelling noise, so ugly it causes physical pain. Or a language of pain. The permission of pain. Thought is buried, being floats.

So you sit with the loss, the tragedy, the incomprehensibility of your love; its new betrayal and new absence. And of course it’s painful — it’s supposed to be painful.

I hope you enjoyed this instalment of Utopia Through Oblivion. Hopefully there’ll be at least a couple more this Summer: you can subscribe to get those delivered to your inbox, or podcast feed. Comments and conversation are always welcomed.